Before Language

Culture does not begin in language. It begins in repetition, in correction, in the regulation of bodies within space. What follows does not argue this condition; it traces how it continues to move.

HOW CULTURE PERSISTS THROUGH HABIT, POSTURE, AND RESTRAINT

By the Editorial Staff

The body knows many things before the mind understands them.

It knows when to withdraw, when to remain silent, when to take up less space. This knowledge does not come from formal education. No one explicitly teaches it. Yet it settles deeper than any articulated lesson, until it becomes instinct.

Culture enters the body long before it turns into language.

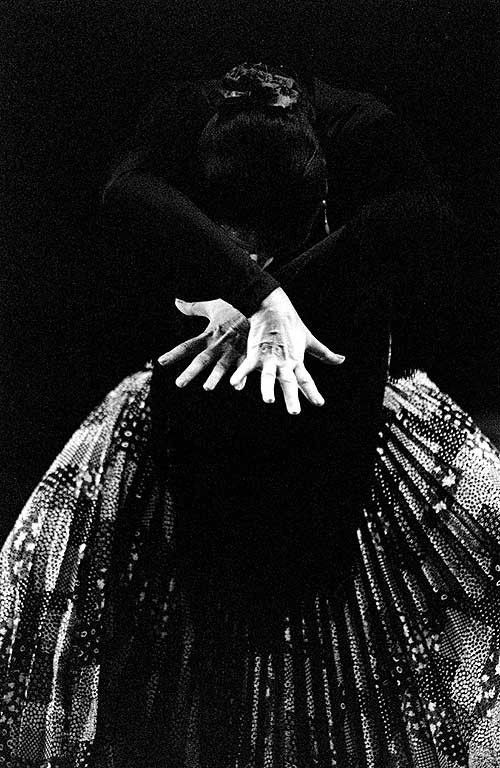

Through repetition. Through corrective glances. Through spaces that define the limits of movement. Through distances that mark what is permitted and what is not. Gradually, the body learns how to stand in a group, how to sit, how to hold its hands, how to regulate its pace. This learning is silent—but it is precise.

Look at public spaces.

Queues. Subways. Elevators. Waiting rooms. Ceremonies. Streets. Bodies communicate without words. Distances are calibrated. Gazes are timed. Pauses are meaningful. No one gives instructions, yet everyone knows what to do. This knowing is collective, but it is inscribed into individual bodies.

The learned body holds memory.

Not the kind that tells stories, but the kind that reacts. A body that steps back before thought intervenes. A body that contracts before a decision is made. A body that hesitates even when the conscious mind wants to move forward. This memory is rarely the result of a single event; it is produced through countless small repetitions.

In many cultures, this bodily education is unevenly distributed.

Some bodies are granted greater freedom to occupy space, to speak loudly, to move without explanation. Others learn early on to minimize their presence, to regulate movement, to manage visibility. The crucial point is that this inequality is rarely articulated. It is not announced or codified. It is performed—daily, quietly, through posture and restraint.

Before the body becomes a political object, it is a habitual one.

And habit is the most powerful form of cultural instruction because it requires no justification. The body becomes accustomed to how it enters a room, where it stands, how long it stays, when it leaves. These habits become so naturalized that they fade from awareness.

In recent years, bodies have become more visible than ever.

Cameras are everywhere. Public spaces are increasingly transparent. Digital platforms turn bodies into images. Yet at the same time, the range of bodily movement has narrowed. The body must be visible—but not excessively so. It must be present—but remain within the frame. It must move—but in predictable ways. This contradiction produces a new pressure: visibility without agency. The contemporary body is simultaneously exposed and constrained.

And it is precisely this condition that activates older bodily knowledge.

Photo: Pinterest

For survival, the body returns to familiar lessons: move less, attract less attention, regulate yourself. Even in spaces that appear more permissive, these learned responses persist.

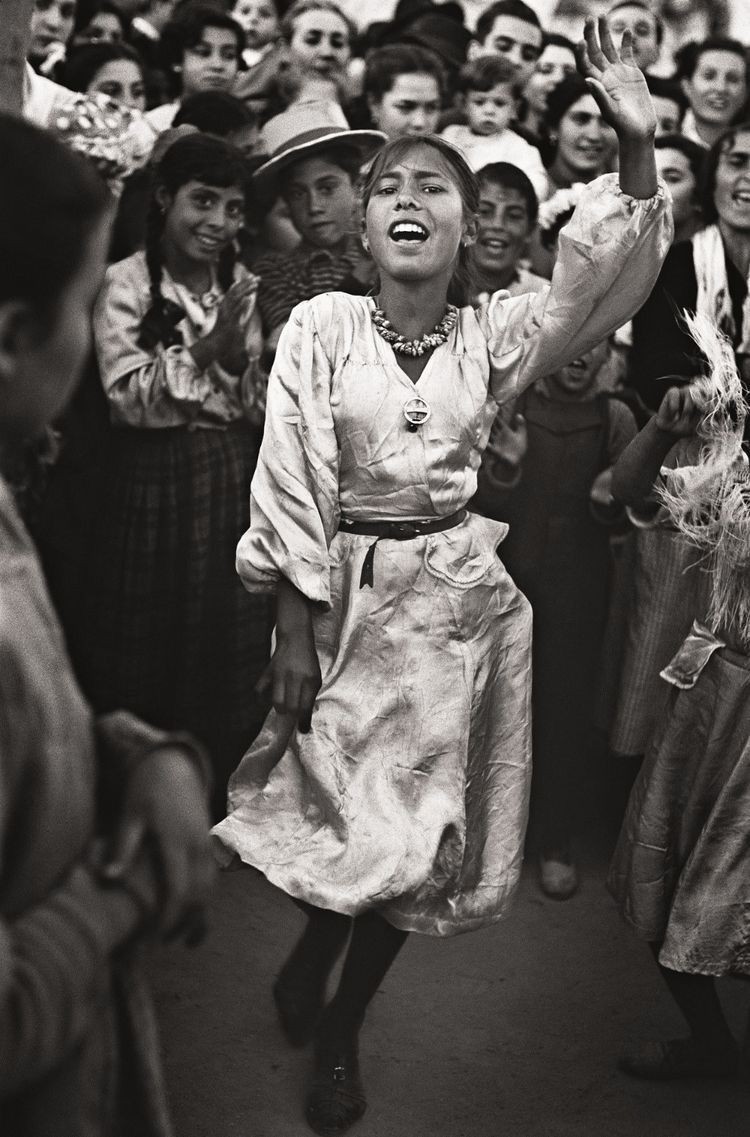

In this context, moments when the body deviates from its training become significant.

Not as acts of heroism, but as slippages. A dance that lasts too long. Standing without a reason. Fatigue that refuses concealment. Mourning that exceeds control. These are moments when the body briefly releases what it has been holding.

This article is not about the body as a site of romanticized resistance—that simplification is dangerous.

Bodies rarely rebel consciously. More often, they tire. They misstep. They fall out of rhythm. And it is precisely in these minor disruptions that cultural tension becomes visible—not through slogans, but through interruption.

The body is a storage site of culture. A place where norms remain even when forgotten. Where traces endure even when values shift. Where the body continues to perform older scripts long after language has changed.

Culture is not always spoken.

Often, it simply moves.

In the space between two steps.

In the pause before sitting down.

In the unconscious drawing back of the shoulders.

And the body,

before it understands why,

Complies.

This article is an original editorial analysis produced by [DIBA magazine].

Research and references are used for contextual accuracy.