The Pregnant Body in Art History

For centuries, art has favored bodies that appear resolved, balanced, controlled, complete. Pregnancy disrupts this logic entirely. It is a state of constant transformation, a form that refuses stillness and challenges ideals built on permanence and proportion. The pregnant body unsettles visual systems grounded in mastery and order, exposing how visibility, time, and bodily change have been carefully regulated. In confronting pregnancy, art is forced to confront instability itself, not as failure, but as a fundamental condition of life.

WHEN FORM REFUSES STILLNESS: PREGNANCY AND THE LIMITS OF CLASSICAL VISION

By Zara Saberi

January 3, 2026

Raphael, La Donna Gravida, 1505-1506

Palazzo Pitti, Florence, Italy

The Pregnant Body as a Visual Problem

Beauty has never been a fixed or universal concept. Across time and cultures, it has carried shifting meanings, fertility, virtue, eroticism, power, purity, and control.

What is understood as beautiful has always been shaped by the beliefs, anxieties, and visual systems of specific historical moments. Nowhere is this instability more evident than in the visual arts, where ideals of the body have repeatedly served as mirrors of social order.

For centuries, art has relied on the human body, particularly the female body, as a stabilizing device. Bodies were measured, proportioned, and rendered legible through systems that privileged clarity, balance, and ideal form. These representations were never neutral. They reflected broader structures of authority: religious doctrine, gender hierarchy, and social control. Art did not merely depict beauty; it actively participated in defining and regulating it.

This visual order depended on classification. Bodies were organized into recognizable categories youthful or aging, active or passive, idealized or expressive.

Meaning emerged through legibility, and legibility required fixity. The body, in art, was expected to appear complete.

Pregnancy unsettles this logic at its core.

Unlike other bodily states, pregnancy refuses resolution. It is neither decorative nor neutral. It cannot be easily eroticized, yet it remains visibly charged. It is active without being performative, present without offering spectacle. Above all, pregnancy introduces time into form. The body is no longer static but transitional, continually recalibrating weight, balance, and spatial presence.

Within visual systems organized around permanence and ideal proportion, this temporal instability posed a problem.

The pregnant body could not be easily reconciled with artistic languages that privileged stillness over process and completion over change.

The In-Between Body: Neither Fixed nor Decorative

The visual unease surrounding pregnancy is not incidental; it is structural. Western art history has long depended on the body as a stable form, one that can be measured, idealized, and resolved into a coherent image. Within this system, bodies are expected to occupy recognizable visual roles: ornamental or symbolic, erotic or maternal, passive or active. Pregnancy unsettles all of these positions simultaneously.

Neither fully decorative nor narratively neutral, the pregnant body occupies a visual threshold. It resists erotic containment without offering transcendence. It signals productivity without aligning with classical ideals of beauty. Most critically, it introduces duration into a visual language designed to suppress time. The pregnant body is not a body at rest; it is a body becoming.

This condition placed pregnancy in an aesthetic in-between that eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art struggled to assimilate. Visual culture of these periods relied heavily on compositional balance, anatomical clarity, and symbolic legibility. Bodies that resisted stable categorization were not eliminated outright, but subtly redirected.

Pregnancy was rarely denied; it was deferred, pushed into allegory, absorbed into costume, or displaced into moral narrative.

As a result, pregnancy seldom appears as a form. It appears as an implication.

Managing Change: How Art Softened Pregnancy

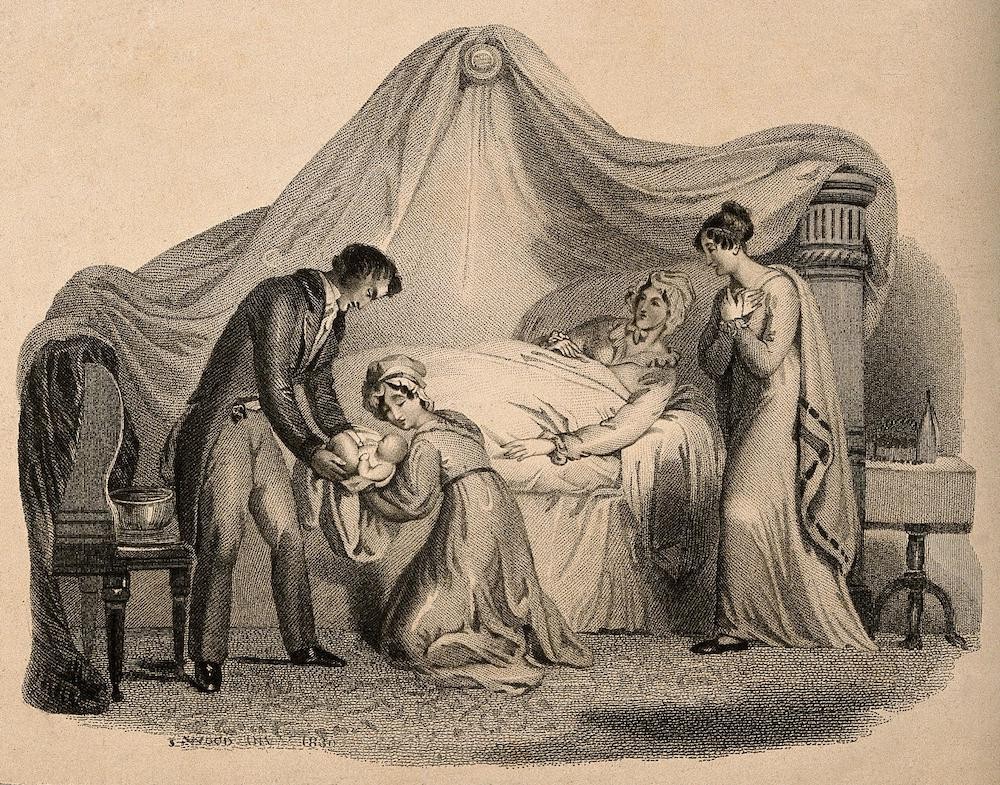

When pregnancy did enter the visual field, it was carefully managed through aesthetic strategies designed to neutralize bodily transformation.

Drapery became one of the most effective tools in this process. In eighteenth-century portraiture and religious painting alike, fabric functioned not simply as clothing, but as a formal mechanism, one that absorbed curvature, redirected the eye, and restored compositional equilibrium.

Lady Lilith

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1866 – 1873

In the works of artists such as Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, whose portraits defined aristocratic femininity in late eighteenth-century France, the female body is rendered supple, luminous, and controlled. Even when motherhood is implied, pregnancy itself is absent as a visible condition. The body remains elegant, continuous, resolved. Change is anticipated, but never allowed to appear.

Similarly, in nineteenth-century academic painting, the female body was increasingly tied to ideals of moral virtue and domestic order. Artists such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres perfected a visual language of anatomical refinement and surface harmony. His bodies, elongated, smoothed, abstracted, exist outside of time. Pregnancy, as a state of physical transition and imbalance, had no place within this aesthetic economy.

When maternal figures did appear, they were often post-pregnant, their bodies returned to symbolic legibility through motherhood rather than transformation. The Madonna, the nurturing mother, the allegorical bearer of life, these figures offered narrative resolution. Pregnancy itself, however, remained unresolved and therefore visually intolerable.

This pattern reveals a deeper aesthetic anxiety: transformation was perceived not merely as difficult to depict, but as fundamentally destabilizing. Art favored bodies that appeared complete, even when lived experience insisted otherwise.

Clothing the Unstable Body: Pregnancy and the History of Dress

The management of pregnancy was not confined to painting and sculpture. It extended powerfully into the history of dress, where clothing functioned as a parallel visual system—one equally invested in order, proportion, and social legibility. If art struggled to accommodate the pregnant body as form, fashion worked to discipline it as surface.

For centuries, Western dress operated as an architecture of the body. Corsetry, structured bodices, and rigid silhouettes did not merely shape appearance; they enforced visual coherence. These garments assumed a body that could be contained, centered, and stabilized. Pregnancy disrupted this premise.

The expanding abdomen challenged the logic of tailored symmetry and exposed the limits of clothing systems designed to suppress bodily change.

Rather than adapting form to transformation, historical fashion more often attempted to disguise it. In the eighteenth century, high-waisted gowns and voluminous skirts allowed pregnancy to be absorbed into excess fabric, rendering bodily change ambiguous rather than visible.

The Empire silhouette, often retrospectively associated with maternal softness, did not celebrate pregnancy; it camouflaged it. The body beneath the dress remained unreadable, its transformation deferred.

In the nineteenth century, as bourgeois morality tightened its grip on female respectability, maternity became increasingly regulated through dress. Specialized maternity garments emerged, not to foreground pregnancy, but to normalize it within acceptable visual boundaries. These designs prioritized modesty, discretion, and continuity. Pregnancy was acknowledged as a social condition, but denied as a visible form.

What emerges is a consistent logic shared by art and fashion alike: pregnancy was tolerated only when it did not interrupt visual order. Clothing absorbed what painting could not resolve. Fabric became a mediator between bodily instability and aesthetic control.

This history reveals that fashion, like art, has long functioned as a technology of visibility. It determines which bodies may appear stable, which must be softened, and which transformations must remain unseen. Pregnancy exposed the limits of this system. It demanded garments that could accommodate change without admitting it.

Only in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries does this relationship begin to shift. Contemporary designers increasingly treat pregnancy not as a problem to conceal, but as a form to engage. Stretch, modularity, and adaptive silhouettes acknowledge the body as temporal rather than fixed.

The pregnant body no longer needs to disappear into fabric. It reshapes it.

In this sense, fashion mirrors the broader transformation in visual culture. As art learns to accept instability as form, dress begins to relinquish its obsession with containment. Pregnancy, once managed through concealment, becomes an active presence, reshaping not only bodies, but the systems that frame them.

Modern and Contemporary Shifts: When Transformation Becomes Visible

A decisive shift occurs with the breakdown of academic conventions in modern art. As artists began to reject illusionism, ideal anatomy, and narrative closure, instability itself became a legitimate subject of representation. The body was no longer required to perform coherence. It could register weight, duration, and imbalance.

Modern visual culture increasingly privileges process over perfection, temporality over timelessness, and experience over ideal form. Within this altered framework, the pregnant body could finally enter the image not as a problem to be concealed, but as a condition to be observed. The body becomes a site of becoming rather than resolution.

Twentieth-century artists such as Paula Modersohn-Becker disrupted long-standing prohibitions by depicting pregnancy as material presence rather than symbolic function. Her self-portraits present the body as heavy, grounded, and unresolved—neither idealized nor allegorical. Pregnancy is not softened by drapery or displaced into narrative. It is acknowledged as a physical fact, embedded in time.

In contemporary art, this trajectory continues. The pregnant body is increasingly represented as temporally specific—marked by weight, imbalance, and visible change. This shift parallels transformations in the history of dress, where maternity wear begins to accommodate expansion rather than conceal it, and garments respond to the body’s instability instead of disciplining it. The body is allowed to change, and clothing changes with it.

Pregnancy enters the image without apology. It is not a metaphor. It is not an abstraction. It is duration made visible.

Why the Pregnant Body Matters in Visual Culture Today

This inquiry is not primarily about motherhood or representation. It addresses a more fundamental question: how visual systems respond to bodies that refuse stability.

The pregnant body exposes a long-standing contradiction within art history. Art seeks coherence, closure, and visual mastery. Bodies, however, exist in time. Pregnancy makes this conflict impossible to ignore.

By tracing how pregnancy was historically softened, displaced, or deferred, and how it later became visible, we gain insight into how art defines form itself. Not as a static ideal, but as a negotiation between control and change.

Pregnancy does not challenge art by being exceptional. It challenges art by insisting that transformation is not a deviation from form, but its condition.

This article is an original editorial analysis produced by [DIBA magazine].

Research and references are used for contextual accuracy.