Between Visibility and Restraint

Clothing is often seen as decoration or tradition, yet some garments shape how bodies are perceived, emotions controlled, and social order maintained. In Japan, the kimono occupies this deeper role, positioned between visibility and restraint. Neither purely historical nor fully modern, it continues to influence cultural ideas of appearance, discipline, and identity.

THE KIMONO AND THE DISCIPLINE OF APPEARANCE IN JAPANESE CULTURE

By Zara Saberi

January 3, 2026

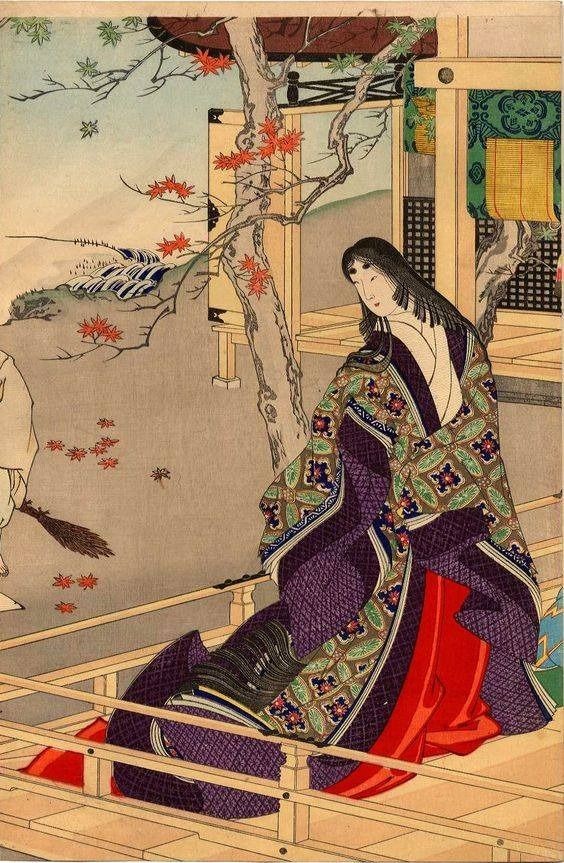

Seventeenth century screen by Iwasa Matabei (via Wikimedia Commons)

STRUCTURE

Long before fashion became synonymous with novelty, speed, or self-expression, clothing operated as a system of order. In Japan, this system did not announce itself through excess or spectacle, but through control, repetition, and restraint. The kimono was never designed to celebrate the body.

It was designed to discipline it.

Unlike Western dress traditions that evolved around tailoring, curvature, and anatomical emphasis, the kimono emerged as a flat, modular garment, constructed from straight lines, standardized measurements, and minimal cutting. This structural logic was not accidental. As scholars of Japanese material culture have noted, the kimono’s form reflects a broader aesthetic philosophy in which surface outweighs depth, and appearance is governed rather than performed.

What is often overlooked in mainstream fashion history is that the kimono functioned less as clothing and more as infrastructure. It organized how bodies occupied space, how movement unfolded, and how individuals related to one another socially. Sleeves dictated gestures. Layers regulated seasonality. Patterns encoded rank, age, and occasion. Nothing was incidental.

During the Heian period (794–1185), aristocratic dress crystallized into a sophisticated visual code. Court garments such as the jūnihitoe were not meant to be “seen” in motion, but read in stillness.

Color combinations followed seasonal poetry and cosmological associations rather than personal preference.

Fashion here was not expressive, it was legible.

This logic intensified under the Edo period (1603–1868), when sumptuary laws regulated who could wear what, and how visibly. In a society structured by rigid class divisions, the kimono became a paradoxical tool: highly codified, yet subtly subversive. Merchants, officially low in status but economically powerful, used muted palettes and hidden luxury, fine silk linings beneath austere exteriors, to signal wealth without violating regulation

Unlined Summer Kimono (Hito-e) with Landscape and Poem, Edo period (1615–1868), By JSTOR

Crucially, the kimono did not individualize. It is anonymous. The body beneath remained abstracted, its contours concealed, its sexuality deferred. Identity was produced not through silhouette but through context: season, fabric, motif, and formality. This stands in direct opposition to Western fashion’s historical drive toward personalization and bodily revelation.

What the kimono teaches us, if we look beyond nostalgia, is that fashion does not need to shout to exercise power. It can whisper. It can repeat. It can refuse.

In this sense, the kimono represents a radically different fashion ontology:

one in which authority is embedded in structure, not innovation; where visibility is carefully rationed; and where the self is subordinated to a larger social choreography. This is not the absence of fashion consciousness, it is its alternative formulation.

The kimono, then, is not “pre-modern.” It is anti-modern in the Western sense, yet persistently modern in its control of image, distance, and meaning. To wear it was not to express oneself, but to enter a system, one that understood clothing as governance.

If the kimono structured the body, it also disciplined vision. In Japanese dress culture, to be visible was never equivalent to being revealed. Visibility was regulated, delayed, and mediated through layers, distance, and convention.

Unlike Western fashion systems, where exposure, novelty, and silhouette evolution became central, the kimono cultivated a visual economy of controlled legibility. Meaning resided not in what was immediately apparent, but in what required cultural literacy to interpret. A motif half-concealed by an obi, a seasonal flower rendered out of time, or a fabric weight chosen against expectation could signal refinement, resistance, or quiet transgression.

This logic aligns with the broader Japanese aesthetic concept of ma, the interval, the space between things where meaning emerges. Clothing did not fill space; it shaped it. The kimono established a measured distance between bodies, between wearer and viewer, between intention and perception. In this sense, fashion functioned less as spectacle and more as choreography.

The act of dressing itself reinforced this structure. Kimono cannot be put on hastily or alone. It requires assistance, repetition, and embodied knowledge.

This ritualized process situates the wearer within a temporal continuum, linking past practice to present action. Fashion here is not consumption; it is participation in continuity.

What modern fashion discourse often misreads as rigidity was, in fact, precision. The kimono allowed variation, but only within a tightly bounded system. Creativity existed not in breaking form, but in working inside constraints.

This cultivated an aesthetic intelligence fundamentally different from Western ideals of originality and disruption.

Gender further complicates this visibility regime. Women’s kimono, often discussed reductively in terms of beauty or femininity, operated as instruments of social calibration.

Sleeve length indicated age and marital status. Formality dictated access. The body became a site of social legibility, not personal display. To dress “incorrectly” was not a fashion error, it was a breach of order.

In this framework, visibility was inseparable from responsibility. To be seen was to be read, and to be read was to be accountable to the system. Fashion, therefore, was not expressive freedom; it was ethical positioning.

The encounter with Western modernity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries disrupted this system violently. As tailored suits, dresses, and industrial production entered Japan, the kimono was recast, not as infrastructure, but as an artifact.

Western fashion brought with it a new ontology: clothing as progress, trend, authorship, and individuality. Against this logic, the kimono appeared static, ceremonial, even obsolete.

Modernization reframed it as tradition, stripping it of its original function as a living social technology.

Yet disappearance is not the same as obsolescence.

The kimono survived by shifting registers. It moved from everyday governance to symbolic condensation, appearing at rites of passage, formal ceremonies, and moments of national self-representation. Its power narrowed, but intensified. What was once continuous became episodic; what was once lived became curated.

Contemporary fashion has repeatedly returned to the kimono, often misunderstanding it. Designers borrow silhouette, sleeve, or wrap, but detach them from the system that gave them meaning. The result is aesthetic quotation without ontology, form without discipline.

Japanese designers such as Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo, however, engage differently.

Princess Tachibana no Nakatsu, Nara Period.

Photo: Diba archive

This article is an original editorial analysis produced by [DIBA magazine].

Research and references are used for contextual accuracy.