Wearing Survival: New York Fashion in the 1990s as Urban Strategy

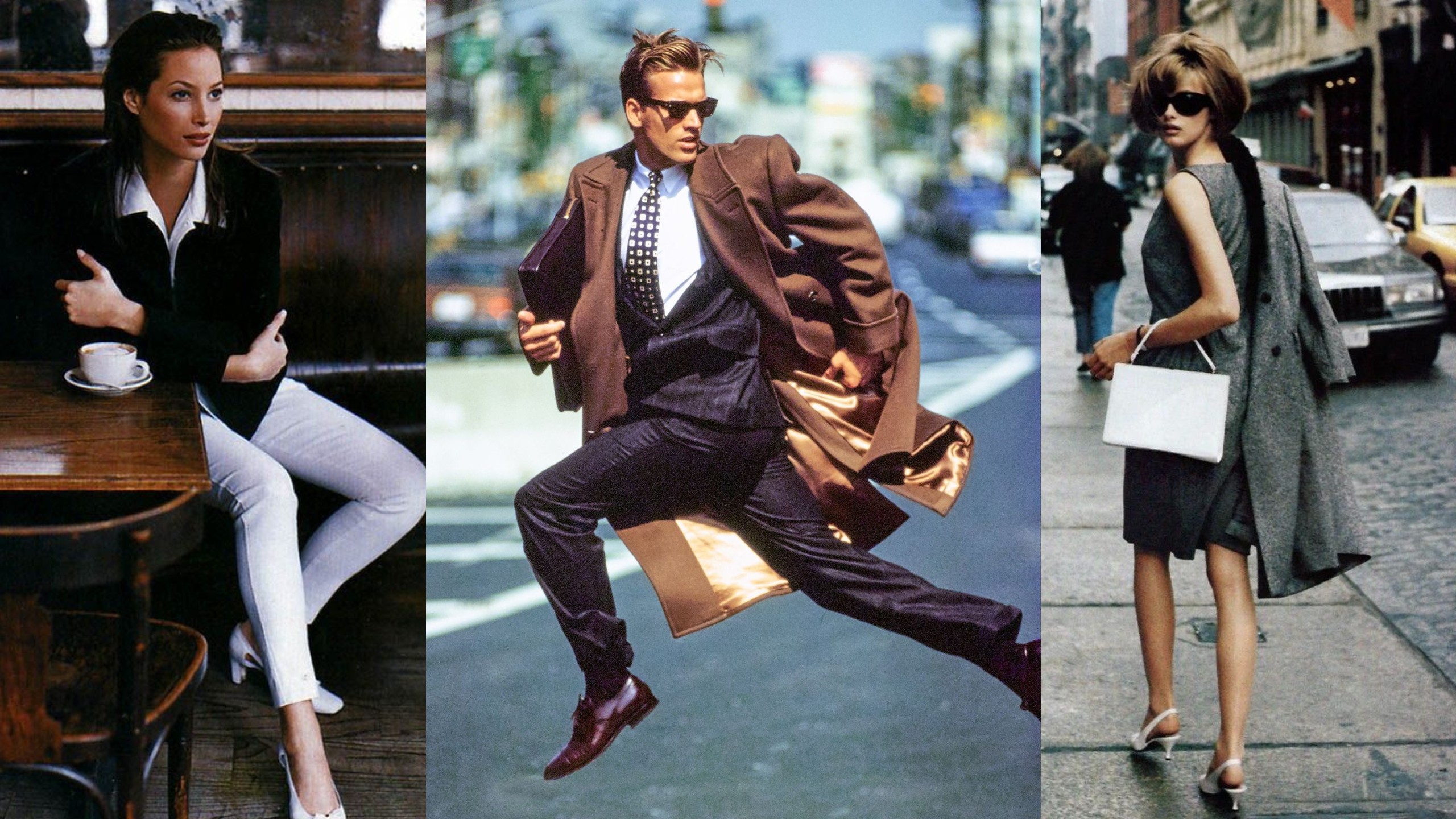

Fashion capitals are remembered for spectacle. New York in the 1990s was shaped by survival. This was a city under pressure, where clothing was not about aspiration but navigation—how to move, how to belong, how to remain visible without becoming exposed. Fashion shed excess and illusion, replacing them with restraint and realism. What emerged was not a trend, but a strategy.

DRESSED TO SURVIVE: FASHION, IDENTITY, AND CONSTRAINT IN 1990s NEW YORK

By Zara Saberi

January 3, 2026

Photo: Diba archive

THE CITY

New York in the early 1990s was not a fashion capital in the celebratory sense. It was a city in recovery, economically unstable, socially fragmented, and physically worn. Crime rates were high, the AIDS epidemic had reshaped entire communities, and the promise of Reagan-era excess had collapsed into exhaustion. Fashion did not respond with fantasy. It responded with realism.

To understand New York fashion in this decade, one must first understand the city itself as a hostile environment. Clothing was no longer about projection or aspiration; it was about navigation. How to move through space without drawing attention. How to signal belonging without vulnerability. How to remain visible enough to exist, but not visible enough to be targeted.

This was a decisive break from the 1980s, when power dressing, exaggerated silhouettes, and conspicuous luxury dominated visual culture. The 1990s rejected that language almost violently. Shoulder pads disappeared. Logos retreated. Color drained. What emerged instead was an aesthetic of reduction, not as taste, but as defense.

Minimalism in New York was never purely aesthetic. Designers such as Calvin Klein, Helmut Lang, and Donna Karan did not propose simplicity as elegance alone, but as functionality. Their garments acknowledged bodies that worked, moved, and endured. Neutral palettes were not about refinement; they were about disappearing into the city.

At street level, this logic was even more pronounced. Hip-hop culture, born from neighborhoods systematically excluded from institutional power, long understood clothing as armor. Oversized silhouettes, layered garments, and athletic wear were not trends, they were responses to surveillance, policing, and economic exclusion. The interdependence of music, urban life, and streetwear in New York helped shape this sartorial language in ways that transcended mere aesthetics.

What unified these seemingly divergent worlds, runway minimalism and street maximalism, was a shared rejection of illusion. Both refused fantasy. Both insisted that fashion engage with actual bodies in actual cities.

New York did not dress to impress in the 1990s. It is dressed to survive.

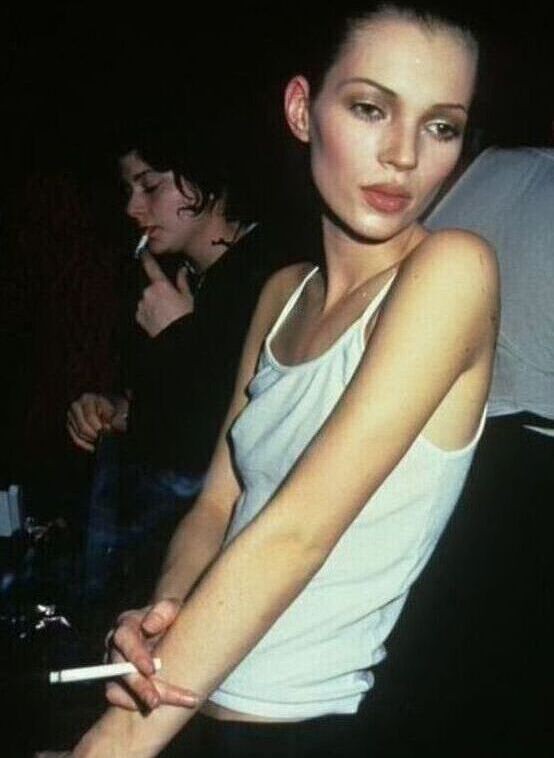

Kate Moss rocks an Isaac Mizrahi mismatching bikini, 1995

Photographer unknown. Kate Moss, ca. 1990s. Pinterest

This survival logic also reshaped the fashion body itself. The decade famously elevated figures like Kate Moss, whose slight, unadorned presence stood in stark contrast to the hyper-constructed supermodels of the previous era. This was not merely an aesthetic shift; it was ideological. The body was no longer an emblem of abundance, but of fragility. Vulnerability entered fashion imagery, not as weakness, but as truth.

In this sense, 1990s New York fashion marks the moment when fashion stopped pretending to be separate from reality. The city insisted otherwise. Clothing became infrastructure, something to live inside, not perform through.

Fashion here was not about becoming someone else.

It was about staying intact.

Photo: Diba archive

IDENTITY

If the city shaped fashion as survival, identity determined how that survival was negotiated. In 1990s New York, race, gender, sexuality, and class were not abstract categories, they were living conditions that structured visibility, risk, and access. Clothing became a way to position oneself within overlapping systems of power.

For Black and Latino communities, fashion had long functioned as both protection and assertion. Hip-hop style, oversized denim, Timberland boots, bomber jackets, athletic silhouettes, was not merely aesthetic. It was a spatial strategy. These clothes expanded the body, claimed presence, and resisted erasure in a city that consistently criminalized and surveilled nonwhite bodies. To dress large was to insist on existence.

At the same time, this visibility was double-edged. What signaled belonging within the community could signal threat to the outside world. Fashion thus became calibrated, adjusted constantly in response to police presence, neighborhood boundaries, and economic precarity. Style was not self-expression; it was situational intelligence.

Gender norms fractured under similar pressures. The 1990s saw a quiet but decisive shift away from overt sexualization in New York fashion. Androgyny, loose tailoring, and gender ambiguity entered both streetwear and high fashion. This was not a denial of sexuality, but a refusal to perform it on demand.

Queer communities, particularly those devastated by the AIDS crisis, developed distinct sartorial languages that merged mourning, resistance, and irony. Black clothing, thrifted garments, reworked uniforms, and intentional minimalism signaled grief and defiance simultaneously. To dress plainly was not to disappear, it was to reject commodified visibility.

Designers absorbed these signals, whether consciously or not. Helmut Lang’s work, in particular, articulated a new masculine vulnerability, clean lines, exposed seams, and stripped-down construction that rejected dominance in favor of restraint. Donna Karan’s layered systems addressed women not as objects of desire, but as agents moving through public space.

What united these practices was a shared skepticism toward spectacle. In a decade marked by loss, of lives, of certainty, of institutional trust—fashion stopped promising transformation. It offered alignment with reality.

Identity in 1990s New York fashion was not declared.

It was negotiated.

Photo: Diba archive

AFTERLIFE

The global fashion system would later aestheticize this moment, often stripping it of context. What was once survival became style. What was once a necessity became a reference.

Minimalism was exported as taste. Streetwear was commodified as a trend. The city’s hardship was flattened into mood boards and seasonal narratives. By the early 2000s, the rawness of 1990s New York had been absorbed into luxury cycles that celebrated “effortlessness” without acknowledging its cost.

Yet the afterlife of this decade remains deeply influential.

Contemporary phenomena such as normcore, anti-fashion, and post-logo dressing trace directly back to 1990s New York’s refusal of spectacle. The idea that clothing could be deliberately unremarkable, functional, neutral, non-performative, originated not from irony, but from exhaustion.

Even today’s emphasis on authenticity, sustainability, and “real bodies” echoes this period’s insistence that fashion responds to lived conditions rather than fantasy. The resurgence of archival Helmut Lang, Calvin Klein, and early streetwear labels is less about nostalgia than about a longing for coherence in unstable times.

The lesson of 1990s New York fashion is not stylistic. It is ethical.

It reminds us that fashion does not always emerge from desire. Sometimes it emerges from constraint. From cities under pressure. From communities navigating risk. From bodies that cannot afford illusion.

New York in the 1990s did not create trends.

It created strategies.

And those strategies continue to shape how we dress when certainty collapses.

This article is an original editorial analysis produced by [DIBA magazine].

Research and references are used for contextual accuracy.