Abbas Kiarostami and the Ethics of Seeing: Cinema Between Image, Truth, and Responsibility

In Abbas Kiarostami’s cinema, images are never neutral. Every frame is an ethical decision, every act of looking a form of responsibility. Through silence, omission, and restraint, he transforms cinema from a storytelling device into a space of reflection, where truth is not fixed, but negotiated between the camera, the world, and the viewer. Kiarostami does not tell us what to see; he asks a more difficult question: how should we look?

CINEMA WITHOUT POSSESSION: ABBAS KIAROSTAMI'S MORAL GAZE

By the Editorial Staff

January 16, 2026

Where is The Friend's House? by Abbas Kiarostami, 1987

Abbas Kiarostami’s cinema is not merely a body of films but a sustained inquiry into the act of looking at itself. More than a storyteller, Kiarostami constructs situations in which seeing becomes an ethical event. His images do not dictate meaning; rather, they establish a space of responsibility between the frame and the spectator. In this space, cinema ceases to be an instrument of control and instead becomes a practice of attentiveness, restraint, and moral hesitation.

From his earliest works, Kiarostami resists the conventional promise of cinema: narrative closure, psychological transparency, and visual mastery. His films are marked by absence as much as presence, by what remains unseen, unheard, or unresolved. This is not a failure of representation but a deliberate refusal to dominate reality. Kiarostami’s cinema does not seek to explain the world; it seeks to coexist with it.

Central to this approach is the ethics of the gaze. The camera in Kiarostami’s films is never neutral. It is frequently late, displaced, or deliberately excluded from moments of narrative importance. Key events occur offscreen: death, confession, resolution. By withholding these moments, Kiarostami challenges the viewer’s expectation that cinema has the right to see everything. Vision, in his work, is always partial, and therefore accountable.

This ethical position becomes explicit in Close-Up (1990), a film that dismantles the very notion of cinematic truth. Rather than uncovering the “facts” of Hossein Sabzian’s impersonation, the film stages multiple regimes of looking: judicial, cinematic, media-driven, and spectator-based. Truth emerges not as a stable object but as something constructed through representation. The viewer is implicated in this process, forced to confront their own desire to judge, sympathize, or condemn. Ethics here lies not in moral clarity, but in uncertainty.

Life and Nothing More, Abbas Kiarostami, 1992

Kiarostami consistently destabilizes the boundary between documentary and fiction, not as a formal experiment but as an ethical necessity. Documentary, for him, is never innocent. It risks appropriating the lives of others under the guise of realism. By exposing the mechanisms of filming, through visible microphones, audible instructions, or the director’s own presence, Kiarostami acknowledges the power imbalance inherent in image-making. Transparency becomes an ethical gesture: a confession that the image is never free from manipulation.

Close-Up, Abbas Kiarostami, 1990

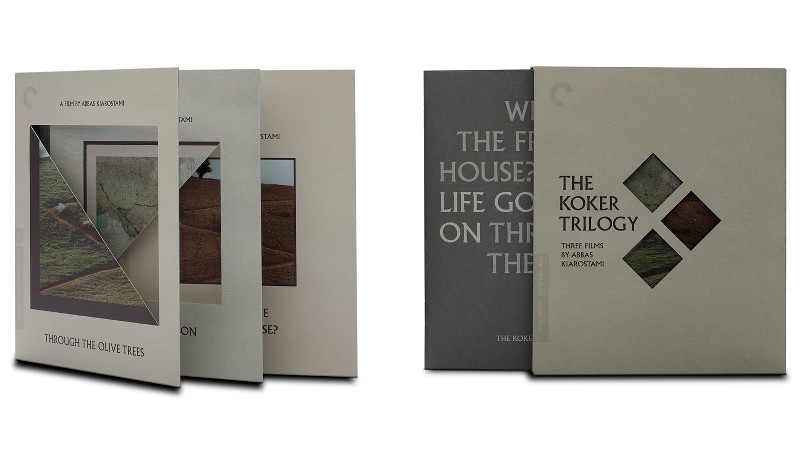

The Koker Trilogy (Where Is the Friend’s Home?, Life, and Nothing More…, Through the Olive Trees) exemplifies this evolving ethics of looking. Each film revisits the same geographical and narrative terrain from a different perspective, refusing linearity or closure. What begins as a child’s moral quest transforms into a meditation on survival, reconstruction, and cinematic responsibility. Love, desire, and intimacy consistently occur at the margins of the frame, present, yet inaccessible.

The camera observes, but does not intrude.

Automobiles occupy a privileged position in Kiarostami’s cinema. The car functions as a transitional space, temporary, unstable, and ethically charged. Conversations unfold without visual reciprocity; one speaker is visible while the other remains offscreen. This asymmetry disrupts cinematic authority and redistributes power.

In films such as Taste of Cherry and Ten, the camera listens more than it asserts, reinforcing cinema as a space of encounter rather than domination.

Taste of Cherry (1997) stands as Kiarostami’s most radical ethical statement. The film’s refusal to depict its protagonist’s death culminates in a sudden rupture: the exposure of the film’s own production. Rather than offering resolution, Kiarostami withdraws the image itself. This gesture is not ironic but deeply moral. It acknowledges cinema’s inability, and its lack of entitlement, to resolve existential questions. Life, he suggests, exceeds representation.

Time, in Kiarostami’s work, is also ethical. Long takes, repetition, and pauses resist the violence of cinematic acceleration. The spectator is asked not to consume images, but to remain with them. Silence becomes a meaningful presence rather than an absence. Meaning emerges slowly, through attention rather than spectacle.

Taste of Cherry, Abbas Kiarostami, 1997

Kiarostami’s characters often evade direct answers. They speak indirectly, hesitate, repeat themselves, or shift the subject entirely. This evasiveness is not narrative weakness but ethical resistance. They refuse to become fully legible objects for the camera. In doing so, they protect a space of interiority that cinema cannot, and should not, colonize.

Ultimately, the ethics of looking in Kiarostami’s cinema is grounded in refusal: refusal to judge, to conclude, to possess. His films remind us that seeing can be an act of violence when stripped of responsibility. Against this violence, Kiarostami proposes a cinema of humility, one that looks carefully, incompletely, and with care for what remains outside the frame.

He does not teach us what to see. He teaches us how to look without harm. And in that disciplined restraint, his cinema opens a rare ethical space, where the world is neither explained nor conquered, but patiently encountered.

This article is an original editorial analysis produced by [DIBA magazine].

Research and references are used for contextual accuracy.